“The White Dog” appears in the anthology Night Fears: Weird Tales in Translation, edited by Eric Williams and published through Paradise Editions. The book collects translated poetry and stories published by the pulp horror and science-fiction magazine Weird Tales.

Translated from Russian by Anonymous

Everything was irksome for Alexandra Ivanovna in the workshop of this out-of-the-way town. It was the shop in which she had served as apprentice and now for several years as seamstress.

Everything irritated Alexandra Ivanovna; she quarreled with everyone and abused the apprentices. Among others to suffer from her tantrums was Tanechka, the youngest of the seamstresses, who had only recently become an apprentice.

In the beginning, Tanechka submitted to her abuse in silence. In the end she revolted, and, addressing her assailant, said quite calmly and affably, so that everyone laughed, “Alexandra Ivanovna, you are a dog!”

Alexandra Ivanovna scowled.

“You are a dog yourself!” she exclaimed.

Tanechka was sitting sewing. She paused now and then from her work and said, calmly and deliberately, "You always whine…you certainly are a dog…You have a dog’s snout…And a dog’s ears…And a wagging tail…The mistress will soon drive you out of doors, because you are the most detestable of dogs—a poodle.”

Tanechka was a young, plump, rosy-cheeked girl with a good-natured face which revealed a trace of cunning. She sat there demurely, barefooted, still dressed in her apprentice’s clothes; her eyes were clear, and her brows were highly arched on her finely curved white forehead, framed by straight dark chestnut hair, which looked black at a distance. Tanechka’s voice was clear, even, sweet, insinuating, and if one could have heard its sound only, and not given heed to the words, it would have given the impression that she was paying Alexandra Ivanovna compliments.

The other seamstresses laughed, the apprentices chuckled, they covered their faces with their black aprons and cast, side glances at Alexandra Ivanovna, who was livid with rage.

“Wretch!” she exclaimed. “I will pull your ears for you! I won’t leave a hair on your head!”

Tanechka replied in a gentle voice: “The paws are a bit short…The poodle bites as well as barks…It may be necessary to buy a muzzle.”

Alexandra Ivanovna made a movement toward Tanechka. But before Tanechka had time to lay aside her work and get up, the mistress of the establishment entered.

“Alexandra Ivanovna,” she said sternly, “what do you mean by making such a fuss?”

Alexandra Ivanovna, much agitated, replied, “Irina Petrovna, I wish you would forbid her to call me a dog!”

Tanechka in her turn complained: “She is always snarling at something or other.”

But the mistress looked at her sternly and said, “Tanechka, I can see through you. Are you sure you didn’t begin it? You needn’t think that because you are a seamstress now you are an important person. If it weren’t for your mother’s sake—”

Tanechka grew red, but preserved her innocent and affable manner. She addressed her mistress in a subdued voice: “Forgive me, Irina Petrovna, I will not do it again. But it wasn’t altogether my fault ...”

Alexandra Ivanovna returned home almost ill with rage. Tanechka had guessed her weakness.

“A dog! Well, then, I am a dog.” thought Alexandra Ivanovna, “but it is none of her affair! Have I looked to see whether she is a serpent or a fox? It is easy to find one out, but why make a fuss about it? Is a dog worse than any other animal?”

The clear summer night languished and sighed. A soft breeze from the adjacent fields occasionally blew down the peaceful streets. The moon rose clear and full, that very same moon which rose long ago at another place, over the broad desolate steppe, the home of the wild, of those who ran free and whined in their ancient earthly travail.

And now, as then, glowed eyes sick with longing; and her heart, still wild, not forgetting in town the great spaciousness of the steppe, felt oppressed; her throat was troubled with a tormenting desire to howl.

She was about to undress, but what was the use? She could not sleep, anyway. She went into the passage. The planks of the floor bent and creaked under her, and small shavings and sand which covered them tickled her feet not unpleasantly.

She went out on the doorstep. There sat the babushka Stepanida, a black figure in her black shawl, gaunt and shriveled. She sat with her head bent, and seemed to be warming herself in the rays of the cold moon.

Alexandra Ivanovna sat down beside her. She kept looking at the old woman sideways. The large curved nose of her companion seemed to her like the beak of an old bird.

“A crow?” Alexandra Ivanovna asked herself.

She smiled, forgetting for the moment her longing and her fears. Shrewd as the eyes of a dog, her own eyes lighted up with the joy of her discovery. In the pale green light of the moon the wrinkles of her faded face became altogether invisible, and she seemed once more young and merry and light-hearted, just as she was ten years ago, when the moon had not yet called upon her to bark and bay of nights before the windows of the dark bathhouse.

She moved closer to the old woman, and said affably, “Babushka Stepanida, there is something I have been wanting to ask you.”

The old woman turned to her, her dark face furrowed with wrinkles, and asked in a sharp, oldish voice that sounded like a caw, “Well, my dear? Go ahead and ask.”

Alexandra Ivanovna gave a repressed laugh; her thin shoulders suddenly trembled from a chill that ran down her spine.

She spoke very quietly: “Babushka Stepanida, it seems to me—tell me is it true?—I don’t know exactly how to put it—but you, babushka, please don’t take offense—it is not from malice that I—”

“Go on, my dear, say it,” said the old woman, looking at Alexandra Ivanovna with glowing eyes.

“It seems to me, babushka—please, now, don’t take offense—as if you, babushka, were a crow.”

The old woman turned away. She nodded her head, and seemed like one who had recalled something. Her head, with its sharply outlined nose, bowed and nodded, and at last it seemed to Alexandra Ivanovna that the old woman was dozing. Dozing, and mumbling something under her nose—nodding and mumbling old forgotten words, old magic words.

An intense quiet reigned out of doors. It was neither light nor dark, and everything seemed bewitched with the inarticulate mumbling of old, forgotten words. Everything languished and seemed lost in apathy.

Again a longing oppressed her heart. And it was neither a dream nor an illusion. A thousand perfumes, imperceptible by day, became subtly distinguishable, and they recalled something ancient and primitive.

In a barely audible voice the old woman mumbled, “Yes, I am a crow. Only I have no wings. But there are times when I caw, and I caw, and tell of woe. And I am given, to forebodings, my dear; each time I have one I simply must caw. People are not particularly anxious to hear me. And when I see a doomed person, I have such a strong desire to caw.”

The old woman suddenly made a sweeping movement with her arms, and in a shrill voice cried out twice: “Kar-r, Kar-r!”

Alexandra Ivanovna shuddered, and asked, “Babushka, at whom are you cawing?”

“At you, my dear,” the old woman answered. “I am cawing at you.”

It had become too painful to sit with the old woman any longer. Alexandra Ivanovna went to her own room. She sat down before the open window and listened to two voices at the gate.

“It simply won’t stop whining!” said a low and harsh voice.

“And uncle, did you see?” asked an agreeable young tenor.

Alexandra Ivanovna recognized in this last the voice of the curly-headed, freckled-faced lad who lived in the same court.

A brief and depressing silence followed. Then she heard a hoarse and harsh voice say suddenly. “Yes, I saw. It’s very large—and white. It lies near the bathhouse, and bays at the moon.”

The voice gave her an image of the man, of his shovel-shaped beard, his low, furrowed forehead, his small, piggish eyes, and his spread-out fat legs.

“And why does it bay, uncle?” asked the agreeable voice.

And again, the hoarse voice did not reply at once.

“Certainly to no good purpose— and where it came from is more than I can say.”

“Do you think, uncle, it may be a werewolf?” asked the agreeable voice.

“I should not advise you to investigate,” replied the hoarse voice.

She could not quite understand what these words implied, nor did she wish to think of them. She did not feel inclined to listen further. What was the sound and significance of human words to her? The moon looked straight into her face and persistently called her and tormented her. Her heart was restless with a dark longing, and she could not sit still.

#

Alexandra Ivanovna quickly undressed herself. Naked, all white, she silently stole through the passage; she then opened the outer door (there was no one on the step or outside) and ran quickly across the court and the vegetable garden, and reached the bathhouse. The sharp contact of her body with the cold air and her feet with the cold ground gave her pleasure. But soon her body was warm.

She lay down in the grass, on her stomach. Then, raising herself on her elbows, she lifted her face toward the pale, brooding moon, and gave a long, drawn-out whine.

“Listen, uncle, it is whining,” said the curly-haired lad at the gate. The agreeable tenor voice trembled perceptibly.

“Whining again, the accurst one!” said the hoarse, harsh voice slowly.

They rose from the bench. The gate latch clicked. They went silently across the courtyard and the vegetable garden, the two of them. The older man, blackbearded and powerful, walked in front, a gun in his hand. The curlyheaded lad followed tremblingly, and looked constantly behind.

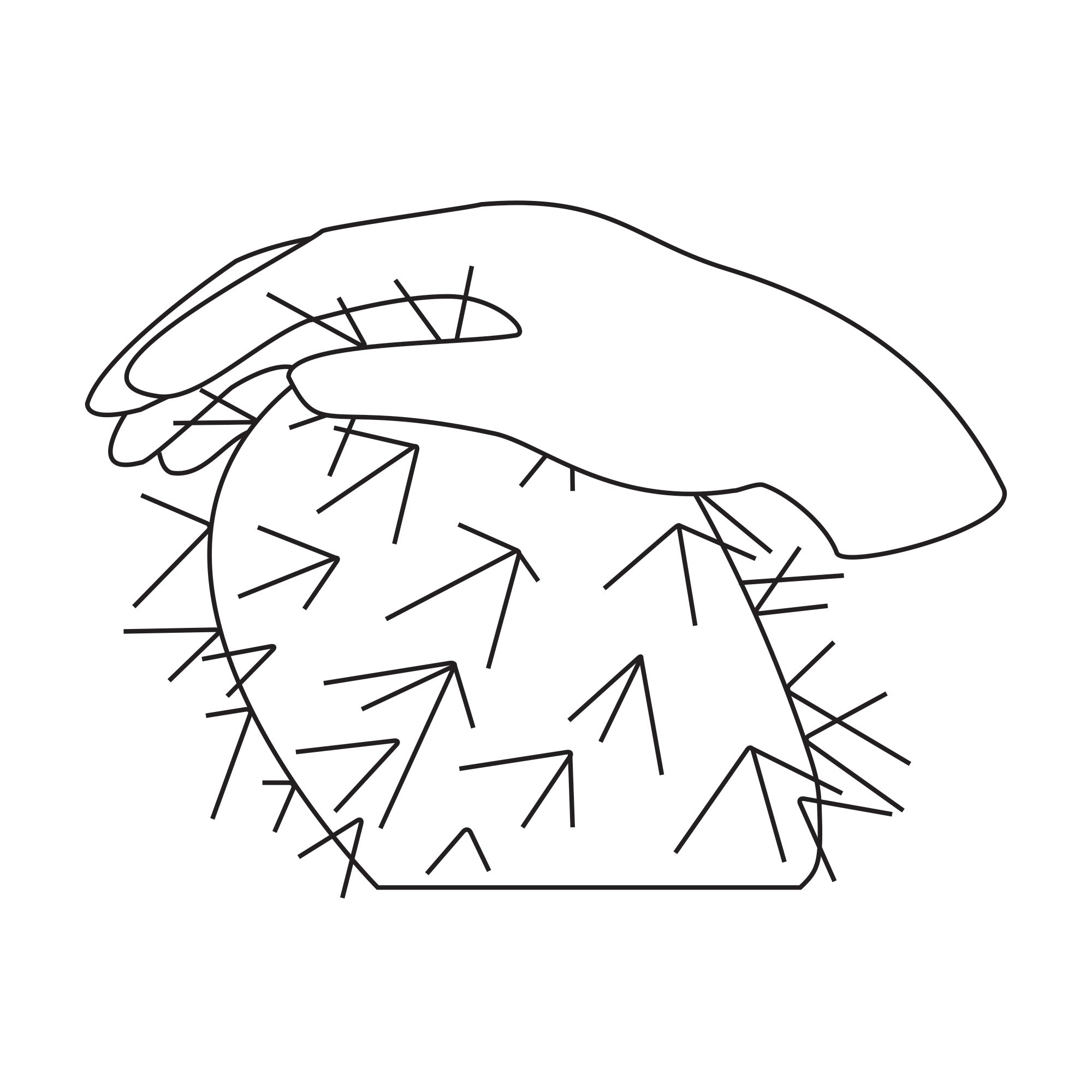

Near the bathhouse, in the grass, lay a huge white dog, whining piteously. Its head, black on the crown, was raised to the moon, which pursued its way in the cold sky; its hind legs were strangely thrown backward, while the front ones, firm and straight, pressed hard against the ground.

In the pale green and unreal light of the moon it seemed enormous. So huge a dog was surely never seen on earth. It was thick and fat. The black spot, which began at the head and stretched in uneven strands down the entire spine, seemed like a woman's loosened hair. No tail was visible; presumably it was turned under. The fur on the body was so short that in the distance the dog seemed wholly naked, and its hide shone dimly in the moonlight, so that altogether it resembled the body of a nude woman, who lay in the grass and bayed at the moon.

The man with the black beard took aim. The curly-haired lad crossed himself and mumbled something.

The discharge of a rifle sounded in the night air. The dog gave a groan, jumped up on its hind legs, became a naked woman, who, her body covered with blood, started to run, all the while groaning, weeping and raising cries of distress.

The black-bearded one and the curly-haired one threw themselves in the grass, and began to moan in wild terror.